Centrelink’s Robodebt computer scam (2016-2018) intimidated 2030 vulnerable Australians to suicide

Do politicians in New South Wales read the news, else are they so in such a self-absorbed bubble mindset that the reality faced by ordinary Australians, and moreso vulnerable struggling Australians, don’t factor in their head space? Why then do they pretend to represent us lot, including those trying to earn a crust?

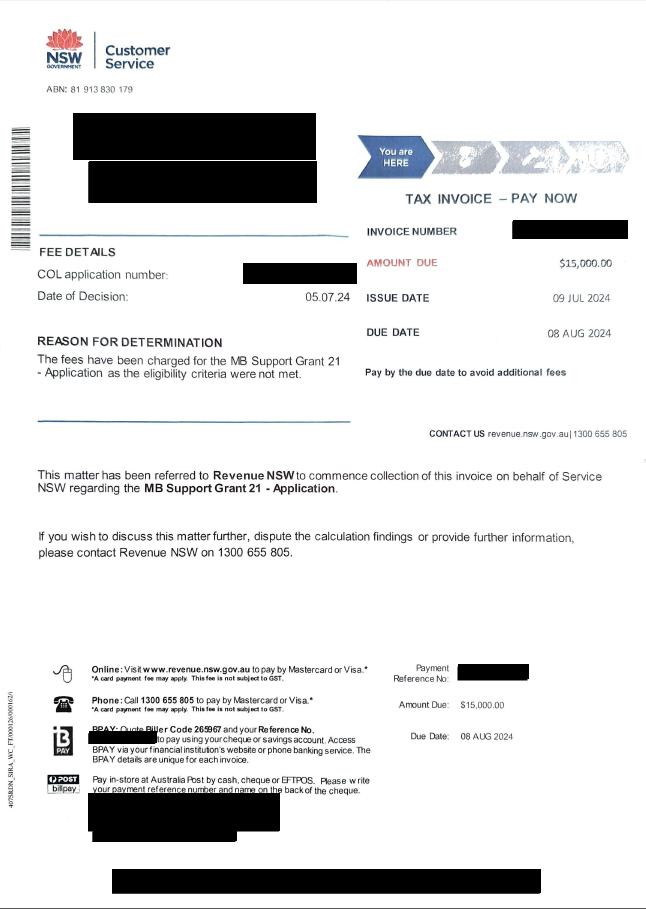

We reproduce the following online articles because we consider the tragic experiment by Centrelink that infamously became known as ‘Robodebt’ to be relevant to the similar unconscionable crap going by Service NSW’s current extortionate claw back of the 2021 compensatory grant under the Minn’s Mafia. Service NSW Minister Jihad Dib should sack himself in disgrace.

Regrettably, some bureaucrats and politicians are slow learners.

The unprecedented amount of data generated in society today has ‘incentivised’ governments to automate citizen-facing services with algorithmic decision-making systems. While there are benefits to using algorithmic decision-making, including efficiency, cost savings and operational transparency, its use can also have unintended negative consequences.

This was the case with Centrelink’s Online Compliance Intervention programme – otherwise known as Robodebt. This scheme was concocted by lazy bureaucrats seeking a ‘one-size-fits-all’ computer programme to more than 900,000 welfare recipients.

It was proposed under the Turnbull Liberal Coalition federal government in 2015 to recover supposed over-payment of unemployment benefits going back to 2010. In 2016, Centrelink started using a computer system to match up tax records with welfare payments, to see if there were any discrepancies.

Robodebt checked with the Tax Office how much employers had paid to social security recipients and then compared it with what had been declared to Centrelink by the recipient. This is known as ‘data matching’.

If the Tax Office’s data didn’t match Centrelink’s information, recipients were asked to explain. If the recipient did not respond or could not explain the difference, Robodebt would swing into action and raise a debt.

Sound familiar to to what Service NSW is currently doing with its Micro Business Grant ‘audit’?

However, Robodebt went even further. It averaged out income declared to Centrelink over the period reported to the Tax Office by the employer. It did so regardless of whether the social security recipients had worked during the whole period. This was known as ‘income averaging’.

For example, if a recipient had worked full time for four weeks in a financial year, their pay would be, say, $25 an hour or $4,000 for four weeks. The fortnightly unemployment benefit is currently $750, or $1,500 over two fortnights. Our recipient loses 50 cents of every dollar they earn through work, so should have missed out on their $750 unemployment benefit twice.

Our recipient would therefore lose $1,500 in unemployment benefits over the year.

However, average out $4,000 over the 26 fortnights in a year, our recipient’s unemployment benefits would be cut by $77 each fortnight.

Our recipient would therefore lose $2,000 in unemployment benefits over the year.

That’s $500 more, and Robodebt would raise that $500 as a debt, even though our recipient did not owe this $500. If our recipient could not explain what happened in the year in question, the debt would stand. If not paid on time, debt collection was farmed out to corporate debt collectors.

The old non-automated system generated 20,000 letters to people who had received Centrelink payments a year. But in the early days of the new system, that jumped to 20,000 letters a week.

Using automated technology, the Robodebt scheme was designed to balance the budget by clawing back $2.3 billion in these welfare overpayments. Reducing national debt has been an objective of Australian political parties for years.

One strategy to reduce debt was to recoup welfare support overpayments. Between 2010 and 2013, it was estimated that over 860,000 recipients of Government benefits owed the Government an average of A$1400 due to discrepancies in their accounts.

Sound familiar to to what Service NSW is currently doing with its Micro Business Grant ‘audit’?

At the time Human Services Minister (overseeing Centrelink), Michael Keenan, claimed the automatic debt notice process was “reasonable, lawful and fair”.

Seriously?

They said the department had sent out 900,000 discrepancy notices – that is, a letter asking the welfare recipient to explain why the info they’ve given doesn’t match what the department has. That doesn’t always lead to a formal debt notice because the recipients of the letter can provide additional information that clears the discrepancy.

Using automated technology, the Robodebt scheme was designed to balance the budget by clawing back $2.3 billion in these welfare overpayments. But ultimately, flaws in the algorithmic decision-making system ended up causing severe distress to citizens and welfare agency staff.

The Robodebt Suicide Epidemic

More than 2030 vulnerable Australians died after receiving Centrelink’s infamous debt notice (Robodebt) according to (subsequent) data released by the Department of Human Services. Of those, 429 – roughly one-fifth – were aged under 35. The figures cover a period from July 2016 to October 2018.

To give you a comparison, there were 3139 deaths of people aged between 15 and 35 in 2016 overall, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

While the department does not collect data on the cause for death in these cases, nearly a third – 663 people – were classified as “vulnerable”, which means they had complex needs like mental illness, drug use or were victims of domestic violence.

Greens Senator Rachel Siewert, who asked the Department for the information, said that there could be more people with vulnerabilities than what is reflected in the official stats.

Senator Siewert:

“Because of the way the system works at the moment, people don’t feel confident or don’t feel safe or trust the person that they’re reporting to to flag that they feel vulnerable, or flag that they might have poor mental health at the time.”

Senator Siewert also said evidence from a Senate inquiry into the system found that getting a debt notice when you’ve done nothing wrong can bring on depression or anxiety.

Senator Siewert:

“People talk about feeling stressed and anxious through the system, feeling humiliated and they get depressed. That sets alarm bells for me, the high proportion of people with vulnerabilities. This should be ringing alarm bells for the Government in terms of further investigation.”

The vast majority of people who died were still receiving Centrelink payments at the time of their deaths. Responsibility for Centrelink lies with the Department of Human Services.

More than 500 people who died were receiving Newstart payments, and a further 520 were on the Disability Support Pension. Men were twice as likely to die than women.

It’s important to note here that the figures provided by the spokesperson include deaths of people who receive a pension payment, which by definition puts them in the older age bracket.

“The number of days that elapsed between customers receiving a debt letter and their death was 222 days, or almost eight months. Any number of factors in an individual’s life could have contributed to their death during such an extended period and it would be foolhardy to draw a link to one particular cause without evidence to support such a claim.

Centrelink raised nearly 410,000 debt notices since the automated system began in July 2016.

ACOSS CEO Dr Cassandra Goldie:

“Robodebt has unleashed thousands of debt notices in error to parents, people with disabilities, carers, students and people seeking paid work, resulting in people slapped with Centrelink debts they do not owe or debts higher than they owe. It has been a devastating abuse of government power that has caused extensive harm, particularly among people who are the most vulnerable in our community.”

The family of 28-year old Melbourne musician Rhys Cauzzo told The Saturday Paper that “aggressive” payment demands from a debt-collection agency on behalf of Centrelink contributed to his suicide.

“People with severe depression don’t handle financial pressure. And these numbers didn’t make sense. He was always anal about keeping financial records,” Rhys’ mother, Jenny Miller, said.

Because it was computer-generated, Hack started hearing stories of how people were told they owed thousands of dollars due to admin errors.

Like hospitality worker Laura, who was told she owed $24,000 – basically her annual income. Laura told the ABC Triple J radio programme ‘Hack’ getting the debt notice was stressful and impacted her mental health.

Laura:

“[I felt] physically sick and I lost my shit straight away. I’ve suffered from depression for a very, very long time and especially at the end of last year when I first got this debt I was already not feeling well because of other things, so I ended up not being at work for a month.

“No one’s listening… I’m basically being called a fraud and a liar and that I don’t matter. It straight away said I was guilty, and a year later [I’m still trying] to prove I’m not guilty. “That’s a year’s worth of my life of stress and struggle that I shouldn’t have had to deal with… It’s a joke.”

The problems with Robodebt were many. The data and automation was being used as a silver bullet to address complex problems without appropriate human oversight and intervention. Ultimately, flaws in the algorithmic decision-making system ended up causing severe distress to citizens and welfare agency staff.

After researching this case, University of Queensland (UQ) Business School experts Dr Tapani Rinta-Kahila, Dr Ida Asadi Someh, Professor Nicole Gillespie, Professor Marta Indulska and Professor Shirley Gregor from Australian National University, discovered that both organisational and technical failures contributed to the many flaws and ultimate downfall of the Robodebt scheme.

Why the Robodebt scheme failed

1. Technical flaws: a simplistic algorithm that couldn’t cope with real-life complexity

One of the design flaws of the algorithm used to make debt collection decisions was that it drew data from two different government systems, one belonging to Centrelink and another one to the Australian Tax Office (ATO). These two systems recorded citizens’ income data in different formats. While Centrelink’s system applied fortnightly figures, ATO’s stored annual income data.

The algorithm averaged a citizen’s earnings reported to ATO over a series of fortnights, matched them with received welfare benefits, and based on the matching, calculated potential overpayments. Because the formula used fortnightly averages instead of actual earnings in the fortnight in question, it led to exaggerated or even false inflation of debt.

Other ways the simplistic algorithm failed to account for real-life complexities included:

Struggling to account for different spellings of employer names in both databases.

Not being able to account for citizens’ unique work-history circumstances, such as casual work. As a result, a significant number of citizens received a ‘Robodebt notice’ that didn’t reflect what they owed to the government (or whether they owed anything at all).

“The debt identification process relied on the automatic matching of two incompatible datasets. As such, the debt sums were based on pure speculation by the system. The debt collection process, in turn, resembled extortion – citizens were effectively scared to accept the debt and pay up. And many did,” says Dr Rinta-Kahila.

2. Complex, confusing interfaces and lack of explanation

The interface of the Robodebt system (debt recovery letters and myGov portal) aggravated the debacle in several ways:

- By not explaining the debt-recollection process, how the debt being recollected was calculated or that it could be inaccurate.

- Failing to explain that you could ask for an extension or be assisted by a compliance officer if you had problems paying the debt.

- Omitting the 1800 compliance helpline telephone number (from the debt letter).

- Making it difficult to understand and contest debts via a complex and hard-to-use online portal that was especially challenging for people with limited access to online technologies.

3. Limited human oversight

The Robodebt system shifted the responsibility of calculating potential overpayments from humans to an algorithm. It also transferred the responsibility of validating the algorithm’s calculations from Centrelink staff to the ordinary citizens who were affected.

While the new system largely automated a very manual process and reduced costs, removing human agency and oversight meant that there were virtually no safeguards in place to counterbalance the algorithm’s flaws.

Previously, human caseworkers used a data-matching system to identify potential debtors and also manually checked information for accuracy before contacting the recipient or their employer to clarify any discrepancies. The automated system independently estimated welfare overpayments and sent debt notification letters to citizens without human scrutiny. There were no checks of accuracy with the recipient or employer.

Before 2016, Centrelink had legally assumed the responsibility for establishing the existence of a debt before pursuing it. They also provided support for citizens who had questions or wanted to work out discrepancies. The Robodebt scheme effectively shifted this responsibility to the individual, requiring them to acquire old bank statements or salary receipts from previous employers if they didn’t agree with the debt claim.

“Before Robodebt, human caseworkers had leveraged a data-matching system to identify potential debtors. The system’s approximations had been treated as ‘raw data’ that needed to be validated through manual investigation; for example, by contacting the citizen or their employer to clarify any discrepancies. This process changed with Robodebt to full automation that removed human safeguards.”

4. Lack of governance or best practice

Centrelink has been criticised for not involving relevant stakeholders, such as the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA), ATO, legal experts or domain specialists, in the development of the Robodebt scheme. In fact, DTA said they had been “locked out” from the process entirely. Additionally, little testing or piloting was conducted when implementing the new Robodebt system.

5. Political motivations

UQ’s experts argue that the government decision-makers responsible for rolling out the program exhibited tunnel vision. They framed welfare non-compliance as a major societal problem and saw welfare recipients as suspects of intentional fraud. Balancing the budget by cracking down on the alleged fraud had been one of the ruling party’s central campaign promises.

As such, there was a strong focus on meeting financial targets with little concern over the main mission of the welfare agency and potentially detrimental effects on individual citizens. This tunnel vision resulted in politicians’ and Centrelink management’s inability or unwillingness to critically evaluate and foresee the program’s impact, despite warnings. And there were warnings.

For instance, when a risk management plan was made, it recognised only the risk of insufficient resources, overlooking the scheme’s potential impact on service delivery, citizen experience or reputational harm. The Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS) also warned that any automated and aggressive debt recovery program “could lead to significant hardship for vulnerable people”.

Even when it became clear the system was flawed, the economic and political incentives and path dependencies prevented government leaders from making any major changes — this ‘locked’ them on a path toward failure.

Incoming Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced the $30 million royal commission soon after he was elected in May 2022, describing Robodebt as a “human tragedy”.

Unnamed individuals will be referred for criminal and civil prosecution after a royal commission handed down its report into the unlawful Robodebt scheme on Friday.

Commissioner Catherine Holmes branded the former Coalition government’s debt-raising scheme an “extraordinary saga” of “venality, incompetence and cowardice”.

“The report paints a picture of how the Robodebt [scheme] … was put together on an ill-conceived, embryonic idea,” Commissioner Holmes wrote.

“It is remarkable how little interest there seems to have been in ensuring the scheme’s legality, how rushed its implementation was, how little thought was given to how it would affect welfare recipients and the lengths to which public servants were prepared to go to oblige ministers on a quest for savings.”

The ABC has confirmed that people are being referred to the Australian Federal Police, the National Anti-Corruption Commission, the Law Society (although it is unclear which jurisdiction), and the Australian Public Service Commissioner.

The three-volume, 990-page report, includes 57 recommendations – the culmination of hundreds of hours of evidence, thousands of exhibits, and nearly a million documents.

A sealed chapter recommends referrals of individuals for civil and criminal prosecution.

Those individuals, whose identities remain a secret, have been referred to four authorities for further investigation.

“I do not propose to name the entities to which I have made referrals, because it would only lead to speculation about who had been referred where, which would almost certainly be wrong,” she said.

“I am confident that the commission has served the purpose of bringing into the open an extraordinary saga, illustrating a myriad of ways that things can go wrong through venality, incompetence and cowardice.”

The report recommended ending the government’s “blanket approach” to the confidentiality of cabinet documents by repealing a section of the Commonwealth Freedom of Information Act.

The report criticises Mr Robert after he advocated the use of income averaging despite his “strong personal view” that the practice led to incorrect debts.

“[Mr Robert] was going well beyond supporting government policy. He was making statements of fact as to the accuracy of debts, citing statistics which he knew could not be right,” the report said.

“Nothing compels ministers to knowingly make false statements, or statements which they have good reason to suspect are untrue, in the course of publicly supporting any decision or program.”

The report recommends that the Commonwealth seeks legal advice about the data exchange processes currently in place between Services Australia and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to ensure they are legal.

It also says a six-year limit on debt recovery should be brought back.

The commission says Services Australia should direct its agencies to finalise legal advice within three months of receipt; and that if public servants want to leave the advice in draft form, they should provide reasons as to why.

It has also been revealed on Friday that taxpayers forked out about $2.5 million in legal expenses for former Coalition government ministers and prime ministers to be represented at the royal commission.

The nine-week inquiry was investigating who was responsible for the scheme, what government officials knew about its legal issues, and the harm caused to victims.

Commissioner Catherine Holmes faced the unenviable task of reviewing about a million tendered documents and hundreds of hours of evidence over nine weeks of public hearings.

The coalition government’s unlawful debt recovery program ran from 2015 to 2019, with hundreds of thousands of welfare recipients wrongly accused of owing money to Centrelink.

It culminated in a $1.8 billion settlement between the Commonwealth and victims, with a federal court judge ruling Robodebt was a “massive failure in public administration”.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese on Friday thanked the victims who shared their stories for showing “bravery in the face of injustice”.

“We’ve arrived at the truth because of the courage of some of the most vulnerable Australians,” he said. “Their courage stands in stark contrast to those who sought to shift the blame, bury the truth and carry on justifying this shocking harm.”

Mr Albanese has condemned the Robodebt scheme, calling it a “gross betrayal and a human tragedy”.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese:

“It was wrong, it was illegal, it should never have happened and it should never happen again.”

But it is with Service NSW in 2023-24.

It’s Robodebt Mark 2.0!

Government Services Minister Bill Shorten said the royal commission had delivered overdue justice and the results were traumatic but vindicating.

Bill Shorten:

“Four hundred and forty three thousand vulnerable Australians who were identified in the federal court and tens of thousands of others … were literally shaken down by their own government. They had the onus of proof reversed, they were treated as guilty until proven innocent and for those who had the temerity to complain they were subjected to vile political tactics.”

As the social services minister at the time Robodebt was hatched, Mr Morrison trumpeted himself as a “welfare cop”.

The royal commission finds Mr Morrison clearly communicated to the public and departmental bosses that his approach to the portfolio was to “crack down” on welfare cheats “rorting” the system.

“In doing so, Mr Morrison contributed to a certain atmosphere in which any proposals responsive to his request would be developed,” the report stated.

“The context was apt to encourage the development of proposals which reflected the approach and tone of his powerful language.”

More than 100 witnesses gave evidence during public hearings, including former prime ministers, politicians, public servants, and ministerial staff.

It heard public servants across the two departments overseeing the scheme were repeatedly warned the scheme was unlawful and had numerous opportunities to stop it.

The former government continued to defend Robodebt over its five-year run, despite significant criticism.

In June 2021, a Federal Court Judge approved a settlement worth at least A$1.8 billion for people wrongly pursued by the federal government’s Robodebt scheme.

The court discovered during the Robodebt scheme, the Commonwealth had unlawfully raised A$1.73 billion in debts against 433,000 people. Of this, $751 million was wrongly recovered from 381,000 people. Settlement payments to eligible group members involved in the Robodebt class action finalised in 2022.

Inherent flaws in the algorithmic decision-making program initiated a cycle of increasing distress among affected citizens, especially ones in vulnerable positions. It also caused work disruption among Centrelink employees who were under unprecedented strain due to the surge of contact from distressed citizens.

Ultimately, while the programme was launched with financial savings in mind, it resulted in no financial gain and significant costs. Sustaining the program severely tarnished the reputation of Centrelink and eroded public trust in the government’s ability to manage social services.

In the report, the commissioner says building a public service capable of preventing a repeat of Robodebt will depend on the government of the day.

“Culture is set from the top down,” she wrote. The report branded anti-welfare rhetoric “easy populism, useful for campaign purposes” that was not confined to one side of politics.

References:

[1] ‘Over 2000 people died after receiving Centrelink robo-debt notice, figures reveal‘, 2019-02-18 by Shalailah Medhora, ABC, ^https://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/2030-people-have-died-after-receiving-centrelink-robodebt-notice/10821272

[2] ‘Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme‘, 7 July 2023 Commissioner Holmes delivered her report and recommendations to His Excellency the Governor-General, Australian Government, ^https://robodebt.royalcommission.gov.au/

[3] ‘Robodebt royal commission findings revealed, individuals referred for criminal prosecution‘, 2023-07-07, by Alexander Lewis and Ciara Jones, ABC, ^https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-07/robodebt-royal-commission-findings-revealed/102531450

[4] ‘Robodebt Scheme‘, Wikipedia, ^https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robodebt_scheme

[5] ‘Is Robodebt targeting pensioners now?‘, 2023-11-17, CPSA NEWS, by

Combined Pensioners & Superannuants Association, ^https://cpsa.org.au/article/is-robodebt-targeting-pensioners-now/

[6] ‘How to avoid algorithmic decision-making mistakes: lessons from the Robodebt debacle‘, by researchers Dr Tapani Rinta-Kahila, Dr Ida Asadi Someh, Professor Nicole Gillespie, Professor Marta Indulska and Professor Shirley Gregor (ANU), University of Queensland, ^https://stories.uq.edu.au/momentum-magazine/robodebt-algorithmic-decision-making-mistakes/index.html#:~:text=Using%20automated%20technology%2C%20the%20Robodebt,citizens%20and%20welfare%20agency%20staff.